Post provided by Carsten Schradin.

Science is about creating knowledge. Yet knowledge only becomes meaningful once it is shared and understood by others. Publishing your research in journals reaches a few very specialised minds of your peers, but if you want your ideas to travel further, you must also communicate them to the public, reaching thousands, hundreds of thousands, or even millions of minds.

You have many ways to do this: from social media posts, a reel getting thousands of clicks, or a compelling press release that attracts journalists. Or you write a blog, in popular science magazines, news websites, or you could even write your own book.

These ideas were explored during a FINE panel discussion with Raghavendra Gadagkar (Indian Institute of Science), Joan Strassmann (Washington University in St Louis, USA), Matthew Cobb (University of Manchester, UK) and myself (CNRS in Strasbourg, France). Here, I focus on three key aspects: (1) interacting with journalists, (2) writing for the public, and (3) where to publish.

Interacting with journalists

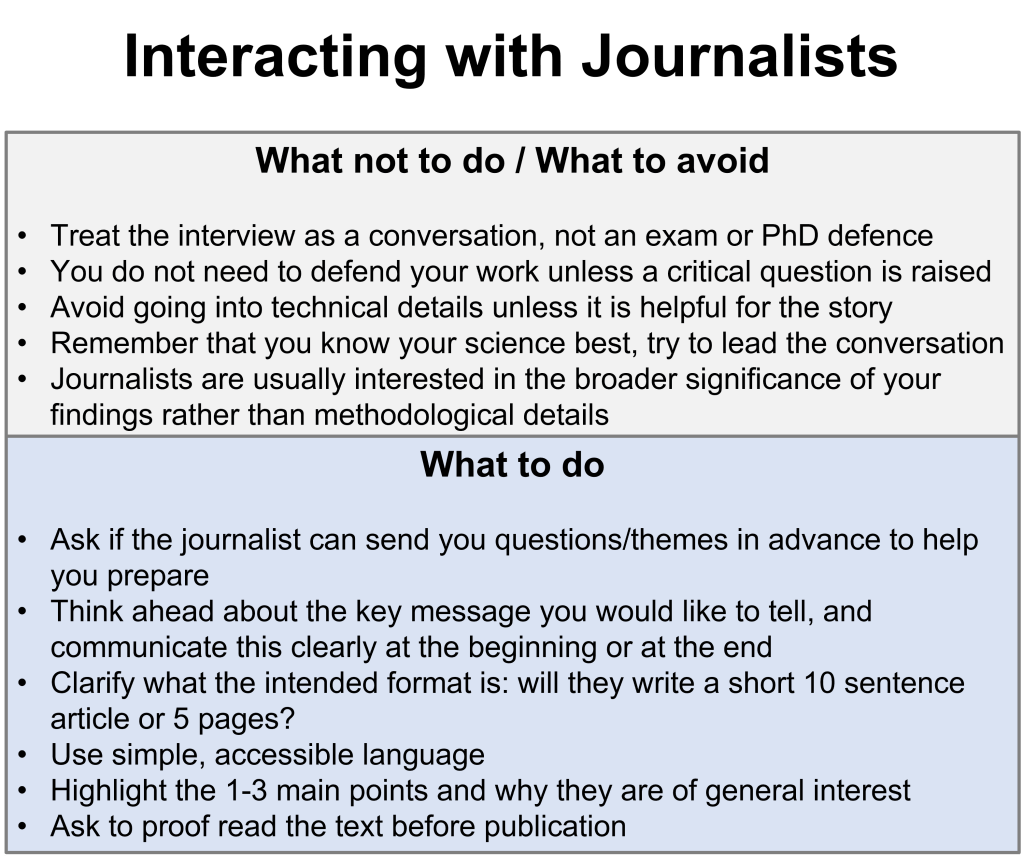

To catch journalists’ attention, prepare a clear and engaging lay summary or a graphical abstract, and share it widely on social media. Another effective route is to issue a press release. Most universities have a press office that provides guidance and a standard form for submitting press releases. The level of support can vary, but when a story resonates, press offices may help distribute it more widely. To increase your chances, make sure your press release highlights one to three points of broad public interest, stated clearly at the start. Finally, do not hesitate to contact journalists yourself, from local papers to national outlets. When I reached out about my research on invasive pond turtles to my local newspaper, journalists quickly picked up the story.

From my experience, the most effective way to attract media attention is to write an article yourself for websites like The Conversation, which is a non-profit news website that publishes articles written by researchers, edited for a general audience. Its content is often republished by other media outlets. For example, an article by my colleague Lindelani Makuya about solitary species was picked up by the BBC, New Scientist and more than 10 other news outlets worldwide, in different languages. To write for The Conservation, you need to pitch an article idea via their website. You will have to provide information on the story, its significance, other key points, and let them know whether you have photos or other multimedia to accompany the article. If you do this, then you already created a press release about your work. If they are interested, their professional journalists will contact you and give you guidance for writing your article.

If you are contacted by a journalist, it helps to think in advance about the key message or story you would like to convey and to communicate this clearly. Try to approach the interview as a conversation rather than an interrogation. You are the expert on your research, and know your science better than anyone, while the journalist brings expertise in storytelling and audience engagement. It can be useful to ask for the interview questions ahead of time to help you prepare, and to gently guide the discussion toward what you feel is the most important story your research can tell.

Writing for the public

Writing for the public means your text must inform and entertain. It needs to be scientifically correct, but the reader also wants to know the story behind the science. People like to hear about people and their personal stories. Explain how you or others did the research, what motivated it, and what surprised you along the way. Personal experiences and moments of curiosity or frustration make science human and engaging. You don’t need drama, but purely technical, emotionless writing won’t hold readers.

Everyone on the FINE panel agreed: good writing comes from good reading. Writers read differently from casual readers, analysing what makes a story engaging or dull. There’s no single formula for success – read widely across genres, from popular science to fiction, and learn from what works. Many books offer advice on writing. Some of the best books to read are the classics On Writing Well by William Zimmer and The Elements of Style by William Strunk, but also Writing Tools from Roy Peter Clark, or On Writing from Stephen King. Learn from them, but you don’t have to use all their advice. Ultimately, you’ll develop your own style. Above all, enthusiasm for your research and the desire to share it will drive good writing.

Where to write

You can write for scientific blogs, newspapers, or popular science magazines, and eventually, books. Start small and build up your skills. Specialist magazines are more open to new writers than large outlets like National Geographic. Write for audiences already interested in your topic such as magazines specialised in birding or on small mammals. If you want to write a popular science book, develop your idea into a clear story and write a proposal to send to publishers or agents. Include the title, a summary, your target audience, chapter outline, market relevance, competing books, your CV and why you are the right person to write this book, and one sample chapter.

So, get started! Your papers may reach dozens of experts, but your public writing can reach thousands or millions of people. Sharing science beyond academia isn’t just outreach; it’s part of creating knowledge itself.

Post edited by Sthandiwe Nomthandazo Kanyile.