I’m Willem Bonnaffé, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oxford. In my research, I integrate biological data, mathematical modelling, and machine learning. I spend most of my time modelling natural systems with neural ordinary differential equations – NODEs or Neural ODEs for short. In this blog post, I am hoping to shed light on what these models are and how I came to use them.

One warm summer night in the south of France, I was watching moths flying around a street light, and spotted a hornet chasing after its next meal. I captured the scene with my camera and was struck by the intricate tangle of untouching light threads tracing the moths’ and hornet’s flight paths. How were the moths able to avoid colliding with each other while evading the hornet? Were their flight patterns random, or did they follow a simple set of rules?

Mathematical modelling is a powerful tool when it comes to studying dynamics. It allows us to translate our hypotheses into (ordinary) differential equations (ODEs), equations that describe change. However, contrary to simple systems in physics, suitable equations are often elusive in biology. When applying mathematical modelling to natural systems, the main challenge is finding the most suitable equation by trial and error.

In the case of the moths, instead of trying to come up with equations that capture the complexity of their movement patterns, I took a different approach.

This is where the neural part of NODEs comes in. Neural networks are functions that can be seen as jigsaw pieces that can fit anywhere. They can be trained to produce any shape. The term neural networks originally comes from their similarity to the basic functioning of neurons, which integrate signals coming from different sources and only fire if they reach a given threshold.

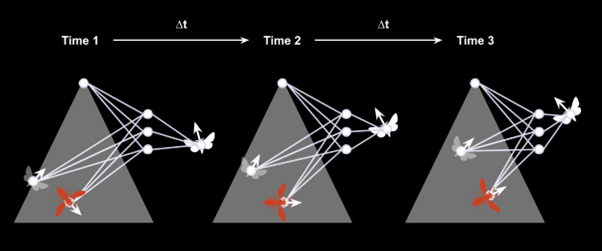

I decided to plug neural networks into differential equations in order to give my digital insects tiny brains and train them to fly in a natural-looking way. The neural network of each focal individual takes in the position of other moths, the hornet, and of the street light and outputs a direction and speed in response.

Although the dynamics are shown here in discrete time (∆t), NODEs simulate the dynamics in continuous time. After training the model and a few failed flights, I arrived at flying patterns that mimicked those that naturally occur around street lights.

By looking at what the neural part of the NODEs had learnt, I was then in a position to uncover the ‘rules’ of moth flight. I quickly realised that, if these NODE models can handle a few moths, why not an entire ecosystem? This opened my eyes to the countless ways this framework could be used to uncover the drivers of dynamics of natural systems. This is how I caught the neural bug which eventually became my DPhil thesis.

One particularly useful application of the NODE approach is to study the interactions between species in an ecosystem. We often record time series of the population sizes of different species which fluctuate based on abiotic conditions and biotic factors, encounters between individuals, prey and predators, or competitors. Those encounters depend on how individuals move in a dynamic environment. Faithfully conceptualising this complexity is virtually impossible for humans, but not for computers.

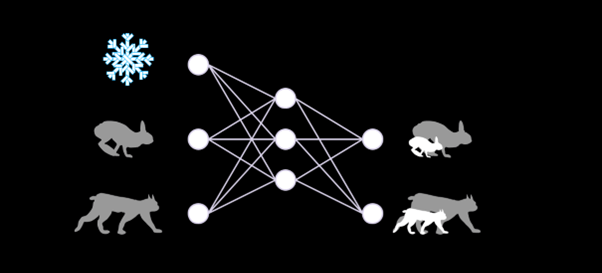

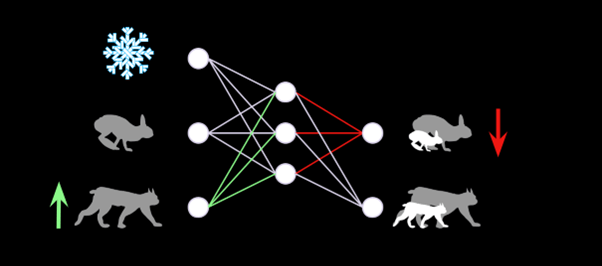

Neural networks can learn from data collected in the field how the current state of an ecosystem, for example the number of hares, lynx, and the weather conditions, influences the growth of both populations.

The neural network essentially pickles the complex web of interactions between these variables, which we can interrogate afterwards. For instance, we can artificially increase the number of predators perceived by the network and see by how much it will adjust its prediction for the growth of the prey population.

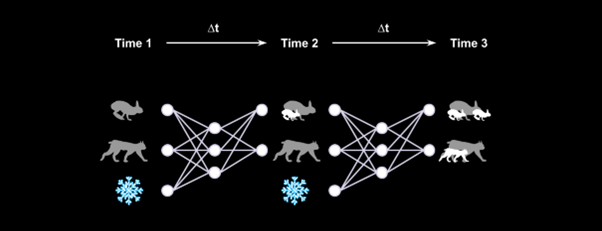

This comes at a cost. Running these models requires expensive computer simulations. This is due to the fact that we have to repeatedly evaluate the neural networks to compute the next state until we have predicted the entire time series.

In our most recent work, we produced a method that cuts down the average time for training these models from 15 minutes to 5 seconds. This uses an ‘observer’ and a ‘process’ neural network working in tandem. The ‘observer’ network is trained to replicate the whole time series of population sizes and the changes per unit of time. The ‘process’ network learns to take the current state of the ecosystem and predict the next state simultaneously across all time points. The gain in speed is achieved in part because the ‘observer’ and ‘process’ networks can process the entire time series at once, instead of sequentially.

Our new method called Bayesian neural gradient matching (BNGM) unlocks speedy computations for NODEs. This puts us in a position to apply these powerful models to large ecosystems, where any attempt at formulating suitable mechanisms by hand would eventually fail.

While we ourselves are limited by our understanding and data, these models are only limited by data. My hope is that we will be able to use the growing treasure trove of time series data to accurately forecast fisheries, invasive species propagation, pests and disease outbreaks. Great progress is currently being achieved with this methodology in physics, neurosciences, and AI, but in ecology (and especially moth ecology), most of the work remains to be done!

You can read the full article here