Post provided by Gaspard Dussert.

My name is Gaspard Dussert, and I am a PhD student at the Université Lyon 1, working in the Laboratory of Biometry and Evolutionary Biology (LBBE). My research combines artificial intelligence (AI) with ecology, focusing on automating wildlife monitoring from camera trap images.

Camera traps are motion-activated cameras placed in the wild. They are incredibly powerful tools in ecology, helping us observe animals in their natural habitats with minimal disturbance and providing a window into their behaviours, activity rhythms, and interactions. But here’s the problem: they generate tens of thousands of images, and manually labelling what’s in them (species, behaviours) is slow and tedious.

In recent years, automatic species identification has improved dramatically thanks to deep learning. But when it comes to recognizing what animals are actually doing (eating, resting, moving) we’re still a long way from automation. Automated behavioural classification from camera trap images is hard : datasets are rare and training specialized AI models requires expertise, time, and computing resources.

So, what if ecologists could use existing pre-trained AI models, known as “foundation models”, to recognize animal behaviours without needing to train anything new?

A new approach: “foundation models” for ecologists

Foundation models, and more precisely Vision-Language Models (VLMs) are huge AI models trained on billions of images and text captions collected from the internet. They’ve learned to connect visual content with descriptive language, allowing them to perform tasks they’ve never explicitly trained for, a capability known as ‘zero-shot learning’.

My PhD supervisors and I asked: Could we just show camera trap images to these models and ask them simple questions like, “Is this animal eating, resting, or moving?”, without teaching them anything new?

To test this, we teamed up with researchers from the Research Center for Alpine Ecosystems (CREA Mont-Blanc) who had a unique dataset of several hundred thousand camera trap images for which the behaviour had been annotated using a citizen science platform.

We evaluated the performance of several recent open-source Vision-Language Models (VLMs), such as CLIP, SigLIP, PaliGemma and CogVLM, which could be freely used by ecologists.

Impressive results, even with no training

To our surprise, even without training specifically on wildlife images, the best models performed remarkably well. One of them, CogVLM, predicted the correct behaviour on 96% of the images.

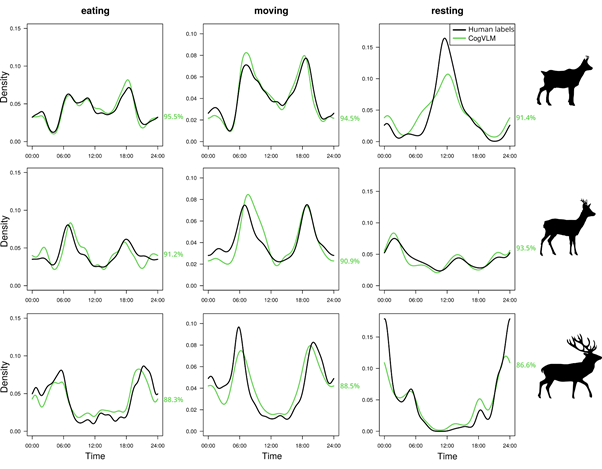

We decided to go even further and used the model predictions to reconstruct activity patterns: charts showing when animals are more likely to eat, move, or rest during the day. These curves are valuable for ecologists studying how behaviour changes across seasons or in response to human disturbance. Again, the best models produced activity patterns that closely matched the human labels, with over 90% overlap.

One lesson we learned from these experiments is that the way we phrased questions to these models, known as “prompts”, can really impact the results. Short or vague prompts (e.g. not mentioning “camera trap”) decreased the accuracy, but surprisingly, too detailed ones, such as including the species name, also led to worse performance. This shows that ecologists will need to experiment to get the best out of these foundation models.

What does this mean for ecology?

This work opens up new possibilities for camera trap studies: with a few lines of code, and a well-written prompt, ecologists can now automatically extract relevant information from camera trap images, something that used to require hours of manual annotation or complex model training. While we illustrated our work with behaviour prediction, the flexibility of the method makes it easily adaptable to other ecological tasks: for example, it could be possible to predict human behaviours or landscape attributes by changing the prompt.

With new foundation models with improved capabilities being released almost every month, we encourage ecologists to explore these tools, evaluate their performance, and learn how to make the most of their potential.

You can access and read our full article here.

Post edited by Sthandiwe Nomthandazo Kanyile