Post provided by Katie Turlington

I’m Katie Turlington, a soundscape ecologist and PhD candidate at the Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University. My research explores how we can use sound to monitor freshwater ecosystems, which are incredibly diverse but often under-surveyed. I’ve spent the last few years working on rivers in South-East Queensland, trying to make sense of the many sounds these systems produce—from insect stridulations to the roar of water surging through the channel after a storm.

Ecoacoustic research is growing fast, and for good reason. It’s a non-invasive way to monitor biodiversity and environmental change. But working with sound isn’t always straightforward. Even short recordings can be dense with information, and sorting through hundreds or thousands of hours of audio manually isn’t feasible for many ecologists. That’s why we developed a new method to help researchers explore soundscapes more effectively.

Why we need better tools for sound

Most ecoacoustic studies rely on two main approaches, (1) acoustic indices, which are usually summary statistics that provide a high-level overview of the soundscape, or (2) recognisers, machine learning tools trained to detect known calls or events in recordings. Both are powerful, but they don’t help us discover unknown or unexpected sounds, especially in ecosystems like rivers, where many species haven’t been acoustically described.

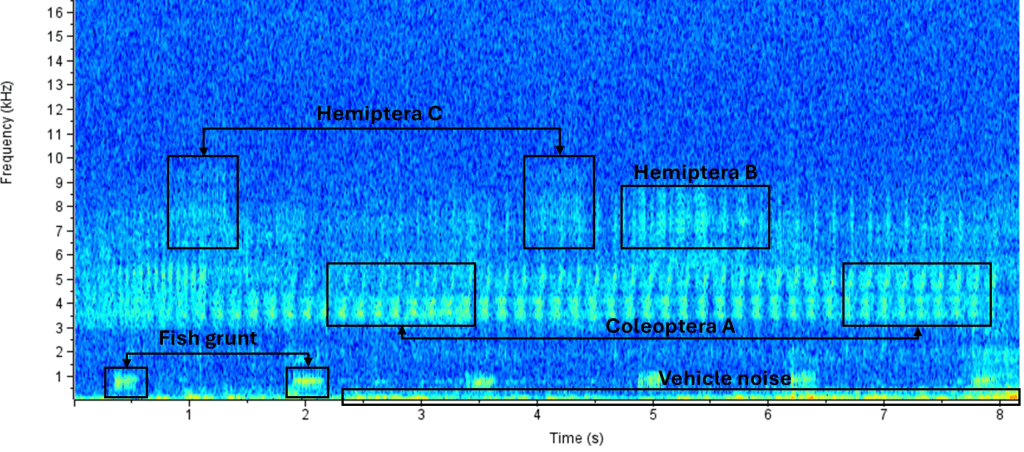

That’s where our method comes in. It’s built for exploratory analysis, helping researchers work out what’s in their data before committing to more targeted approaches. It scans long recordings, detects sections that contain sound, calculates beta acoustic indices, and groups similar sounds using unsupervised clustering (Fig 1). In simple terms, it compares sounds based on their features, like frequency, amplitude, and duration, and groups together those that are most alike.

What’s the novelty?

Beta acoustic indices are conceptually similar to the beta diversity measures used in community ecology, where we examine how species composition varies between sites or over time. In ecoacoustics, these indices quantify the dissimilarity between audio recordings and capture how the soundscape changes across space and time. But I wondered: if beta indices can detect differences between whole recordings, could they also detect differences between individual sound events within these recordings? To test this, we first extracted sounds from audio recordings collected in rivers and calculated pairwise differences between these sounds using beta acoustic indices. This is the first time, to our knowledge, that beta acoustic indices have been used to compare individual sound events in this way, and the results are extremely promising. It opens up a whole new use case for these indices in ecoacoustic research.

Another key feature of the method is its nested clustering approach. River environments are complex, and the constant sound of flowing water often masks biological sounds (Fig. 1). Rather than treat the flowing water as noise to remove outright, our method embraces it. The first layer of clustering separates obvious background sounds, such as water flow, from everything else, so that subtler biological or anthropogenic sounds can be detected. Then, within each cluster, we apply a second round of clustering to group foreground sounds. This layered approach helps overcome one of the biggest obstacles in freshwater ecoacoustics, which is signal masking by the sound of water itself. In testing, the method identified nearly 90% of distinct sound-types in our study and saved hours of manual processing.

A tool for discovery

While we developed the tool for our study in rivers, the method can be adapted to any ecosystem-type and is designed to scale to match the size and complexity of your dataset. It’s semi-automatic, meaning it still allows for human interpretation at key steps, like checking if the clusters make ecological sense, but it dramatically reduces the effort needed to get there.

This approach won’t replace species-level identification or replace expert knowledge. But it’s a powerful starting point, especially in ecosystems where sounds are poorly described. Think of it as a tool for curiosity. Are those rhythmic clicks part of the same sound group? Are those fish grunts the same across streams? Which sounds are consistently present in healthy sites, but missing from degraded ones?

We’ve already applied this protocol across dozens of freshwater streams in South-East Queensland (Fig. 2). It’s helped us detect sound-types that might otherwise have been missed, uncover meaningful patterns that would have been difficult or time-consuming to find manually, and raise new questions about the role of sound in freshwater monitoring. We hope this method will empower others to explore complex and understudied soundscapes in their own regions, enabling more efficient workflows and a stronger ecological understanding of soundscapes across the globe.

http://www.linkedin.com/in/katieturlington0902

Read the full article here.

Post edited by Lydia Morley