Post provided by Josefine Umlauft.

We are a group of geophysicists, mathematicians, and ecologists who normally speak quite different scientific languages. This project brought us together through a shared curiosity: could the instruments and analytical tools originally developed for studying earthquakes also help us understand how trees move in the wind? The result, The Seismic Fingerprint of Wind-Induced Tree Sway, grew out of conversations between seismologists used to reading ground vibrations, and ecologists studying tree biomechanics and forest responses to climate stress. It is a truly interdisciplinary experiment, bridging the worlds of Earth’s deep vibrations and the living, flexible tree structures aboveground.

From tree biomechanics to seismic waves

When wind bends a tree, the movement continues belowground. Each sway sends faint vibrations through the soil, tiny tremors that can be picked up by the same seismometers used to record earthquakes.

Our idea was simple but unconventional: instead of viewing these tremors as annoying “noise”, we asked what if we treat them as a signal, a way to monitor tree mechanics and possibly physiological status through the ground itself?

Understanding how trees respond to environmental stress requires looking at both their internal function and their mechanical behaviour. Physiological sensors such as sap flow meters, dendrometers, or leaf water potential probes show how water transport and growth respond to changing conditions, while accelerometers reveal how trees physically move and bend in the wind. Together, these measurements describe how a tree both feels and reacts to its environment, but combining them at large scales has been difficult. In our study, we tested whether seismic sensors could complement these approaches. By detecting the faint vibrations that trees transmit into the ground, seismometers may capture similar information to accelerometers, but without the need to attach sensors to the trees. While we focus here on reproducing mechanical sway signals, this method could eventually help bridge physiological and biomechanical monitoring, a step toward observing tree function and stability together, across entire forest plots.

The field experiment in the Black Forest

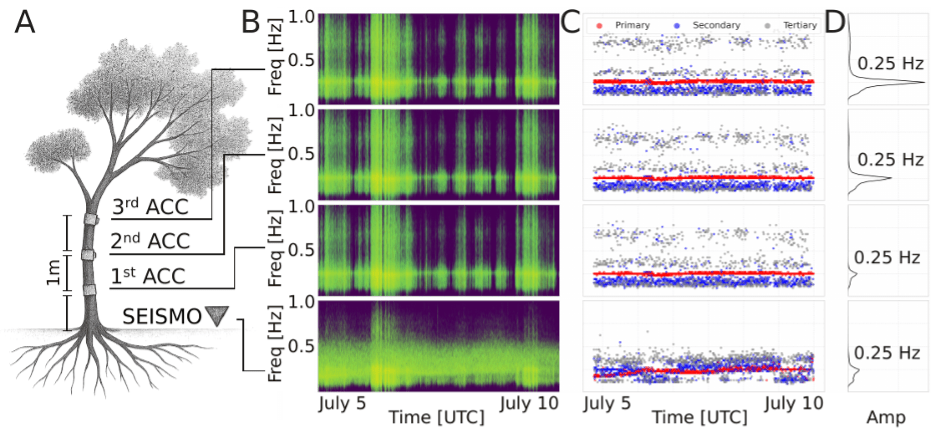

We tested this idea in a mixed stand at the ECOSENSE site in the Black Forest, Germany. Broadband seismometers buried in the soil recorded ground motion while accelerometers attached to tree trunks captured direct sway. Wind and meteorological data completed the picture.

By combining spectral filtering, coherence analysis, and machine-learning models, we identified frequency bands dominated by tree motion, what we call the seismic fingerprint. This fingerprint carries information about how trees interact with wind, and even how those interactions differ among species and structural forms.

What we found

–Distinct sway frequencies: Each tree exhibited a clear resonance frequency (typically around 0.2–0.3 Hz), visible in both seismic and accelerometer data.

–Species-specific dynamics: Beech and Douglas fir showed characteristic differences in damping and resonance frequency, which could be identified directly in the seismic data and were largely explained by differences in tree height and trunk diameter (DBH).

–Structural scaling: The ratio of diameter to height squared (DBH/H²) correlated strongly with sway frequency in the seismic signal, showing that simple geometric traits can predict how trees move in the wind.

–Wind predictability: Using only seismic features, we could reliably estimate wind speed, demonstrating that the ground vibrations themselves contain rich information about tree motion and environmental forcing.

These results confirm that seismic data carry both environmental and biomechanical information. In a sense, the ground becomes a mirror of the forest above it.

A cautious step toward drought detection

One of the most exciting but also most delicate prospects is using the seismic fingerprint to detect physiological stress, such as drought. In our paper, we remain cautious: we did not directly observe drought effects in this dataset, but our results point to clear, testable mechanisms.

Drought is expected to influence tree motion by altering damping behaviour and shifting resonance frequencies for instance, through leaf loss, reduced turgor, or changes in canopy mass. Future studies that combine seismic measurements with independent indicators of water status, such as sap flow or leaf water potential, will be essential to test this link.

If confirmed, seismic sway signatures could offer an early, non-invasive indicator of drought stress, revealing subtle biomechanical changes before they become visible in the canopy.

Why it matters

As climate change intensifies both mechanical disturbance (storms, high winds) and physiological stress (drought), forests face growing risks. Monitoring how trees bend, damp, and recover can reveal much about their resilience.

Our findings suggest that the seismic fingerprint of tree sway is not just a by-product of motion but a valuable ecological signal. With further development, this approach could contribute to long-term forest monitoring and early-warning systems grounded in the principles of environmental seismology.

Seismometers offer a less invasive and more scalable solution than traditional biomechanical sensors, enabling continuous, multi-tree monitoring across plots potentially even entire regions.

The road ahead

Our next steps are to:

– Combine seismic and physiological measurements to investigate how drought and other stress factors affect tree motion.

-Test the approach across more species, soil types, and climates to determine generality.

-Integrate seismic monitoring with other tools such as LiDAR or remote sensing for multi-scale forest observation.

-Develop open-source workflows so that ecologists can extract seismic fingerprints from existing seismic networks.

Ultimately, seismic sensing could become part of a new interdisciplinary toolbox for forest monitoring, one that merges ecology, mechanics, and geophysics.

Closing thoughts

Bringing together seismologists, mathematicians, and ecologists challenged us to rethink what each discipline considers a “signal”. What is now background noise in earthquake data may, under closer examination, reveal the quiet rhythm of trees in the wind. Our experiment shows that these vibrations are not random, but carry information about how forests interact with their environment.

The Earth itself, it seems, holds a quiet record of how trees sway and perhaps, in the future, these hidden signals could be filtered out and studied to help us detect when forests begin to struggle.

Read the full article here.

Post edited by Sthandiwe Nomthandazo Kanyile.