Post provided by Edward Lavender

Skating in the deep

A decade ago, the Movement Ecology of Flapper Skate project was established to track flapper skate (Dipturus intermedius) in Scotland. Flapper skate are large, flattened, benthic animals, with pale undersides and mottled, grey-brown colouration above. Growing in excess of two metres long, they roam over the seabed down to depths of 1200 m. It is thought they may live for over 40 years. Once widely distributed, they were heavily impacted by commercial fishing and are now Critically Endangered.

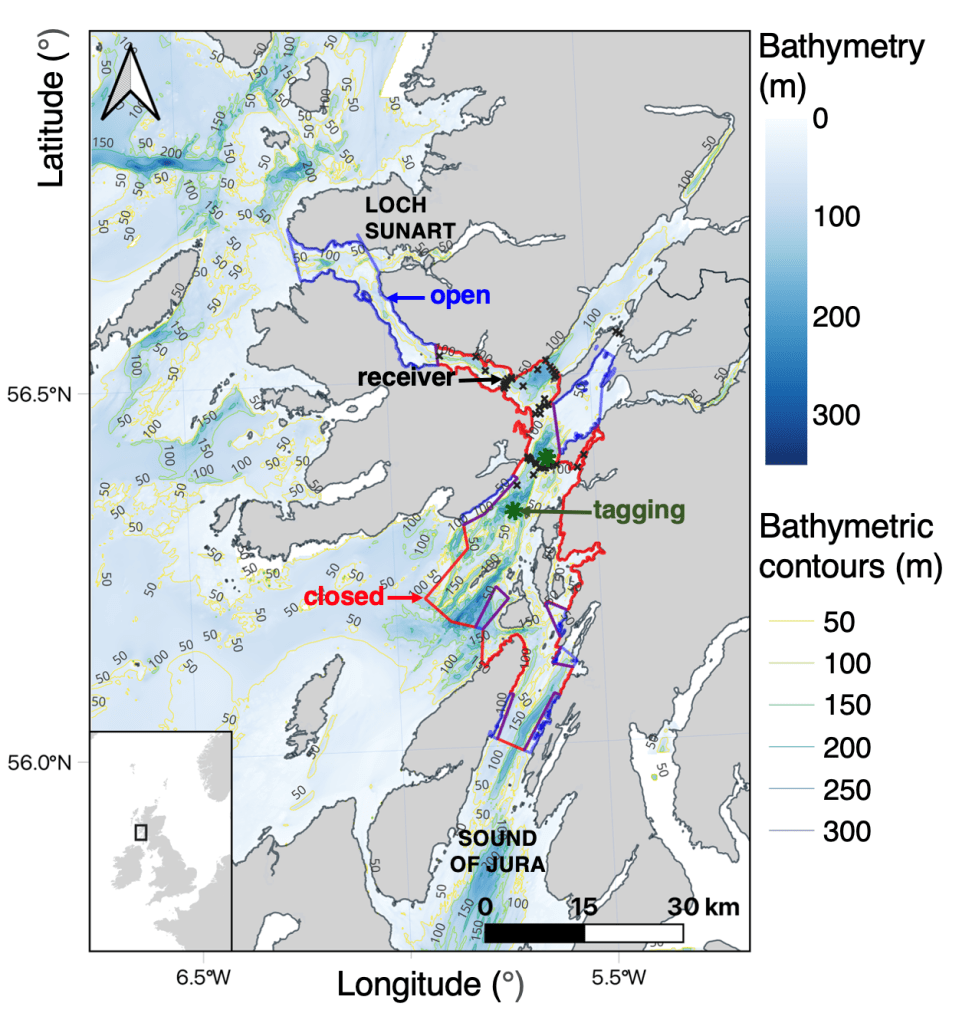

In 2016, a Scottish Marine Protected Area was designated for flapper skate and the Movement Ecology of Flapper Skate project was tasked with the investigation of skate movements in the area. I was a PhD student at the time. Skate were captured and tagged with depth loggers and acoustic transmitters, which were programmed to transmit individual-specific pings that could be detected by underwater receivers. These data underpinned a decade of work on skate movement, depth use, vertical activity, behaviour and oceanography. However, reconstructing detailed movement trajectories remained an open problem.

From tagging to modelling

During a postdoc at Eawag, I started thinking more about the problem of animal geolocation from a state-space modelling perspective. In a state-space model, you model the animal’s movements and the measurement process that connects its (unknown) locations to the observations. By fitting the model to the data, you can estimate the animal’s locations through time. But therein lies the key statistical challenge.

Tracking animals with particles

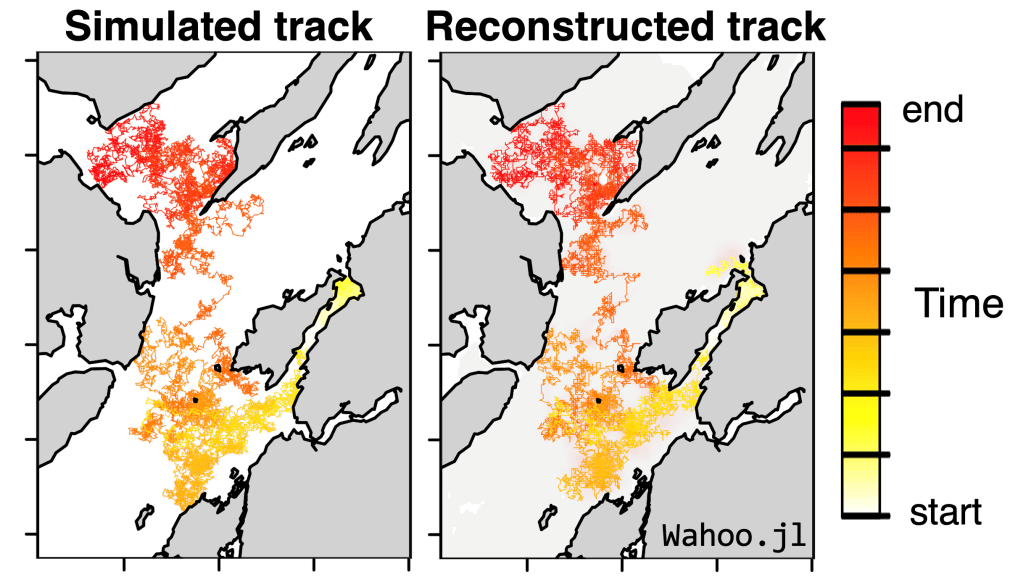

There are different ways to fit state-space models, but they haven’t been widely applied in acoustic telemetry systems. One approach we developed recently is particle filtering and smoothing. The key idea, elaborated in another Methods Blog, is to represent the animal’s unknown locations probabilistically with a cloud of ‘particles’. You recursively simulate particle movement and assign weights using the data: particles which move in ways that align with the data are weighted highly; the others carry lower weight. At any one time, the collection of weighted particles forms a heatmap approximating our probability distribution for the animal’s location. If you’re interested in this approach, check out our patter package. It’s powerful, but affected by particle degeneracy: particularly for benthic species in rugged environments, many particles move in ways that are incompatible with the (depth) observations, reducing the quality of the approximation. This is a hard problem for sampling methods in general.

Going from particles to a grid

A solution is to represent the study area as a grid and compute the probability of the animal being in each cell, accounting for movement and the observations. Since we compute probabilities everywhere, and not just in the locations occupied by a finite number of particles, particle degeneracy is avoided. The approach was established by Uffe Thygesen and colleagues, but has not been widely used in acoustic telemetry systems in the absence of efficient, user-friendly software.

Swimming faster with Wahoo.jl

Alleviating this challenge, our new paper presents the Wahoo.jl package. The key innovation in Wahoo.jl is to represent the movement step via a convolution operation that runs on a computer’s Graphical Processing Unit (GPU). This step ‘blurs’ the probabilities in each cell by sweeping a transition matrix encoding the animal’s movement behaviour over the grid. The same kind of thing happens when you airbrush an image on your phone and blazingly fast algorithms have been developed for this operation that run on the GPU. This is a particular kind of computer chip with thousands of threads that can handle many simple, repetitive tasks simultaneously. Leveraging this technology for convolution provides massive speed ups, unlocking new opportunities to analyse big, real-world datasets.

Skating back to the start

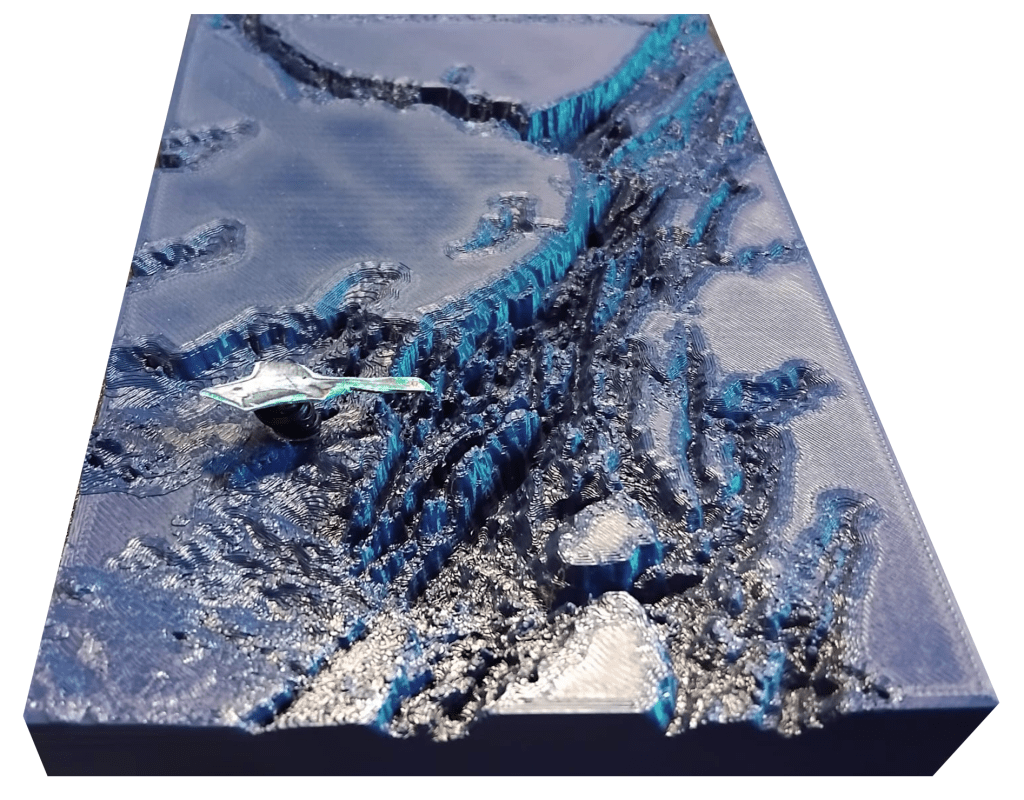

For tracking benthic animals, Wahoo.jl allows us to fully exploit depth observations and knowledge of the bathymetry, alongside acoustic observations, for inference, leading to stunningly precise movement trajectories. We’re now using this approach to analyse flapper skate movements with unprecedented detail.

Reaching out and looking ahead

To use Wahoo.jl, jump to GitHub. Reach out with comments or queries. We hope the package will be useful, but it’s not a silver bullet. For an overview of alternative approaches that make different trade-offs, see our review.

Acknowledgements

The Movement Ecology of Flapper Skate project was established by James Thorburn. My PhD (2018–22) was supervised by James Thorburn, Sophie Smout, Janine Illian, Mark James and Peter Wright, with support from Jane Dodd and Dmitry Aleynik. My postdoc at Eawag (2023–5) was supervised by Helen Moor and Carlo Albert and supported by Andreas Scheidegger.