Post provided by Margot Belot

If you had asked me a few years ago what I would be doing today, I probably would have told you I’d be digging up ancient artefacts somewhere or cataloguing them in a museum. My background is in Archaeology and Art History; for a long time, my world revolved around the tactile nature of physical objects, carefully handling, describing, and ensuring their preservation.

In a previous professional life, I worked as a cultural mediator and guest researcher, often found deep in archives deciphering historical handwriting. I vividly remember struggling through documents written in Sütterlin, an old German script, trying to extract meaning from the loops and scrawls of long-dead curators to understand the provenance of fossil echinoids. While I loved the “detective work,” I felt the mounting weight of a silent crisis: the sheer volume of history that remained undocumented and, therefore, inaccessible to the world.

Today, however, I spend less time with trowels and brushes and more time wrestling with Python code and Convolutional Neural Networks. This shift wasn’t a departure from my love of history, but a modern evolution of it. My curiosity about using digital tools to better understand ancient documents led me to my current role as a Data Manager at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin (MfN).

A New Toolkit for Old Problems

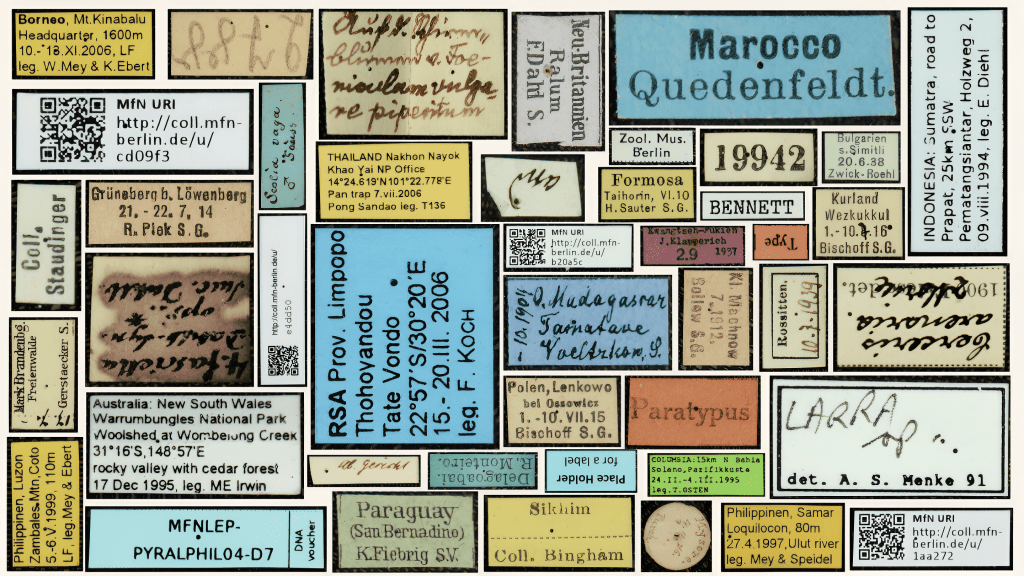

The journey to this work wasn’t a straight line. While working as a digitization specialist at the MfN, I saw the scale of the challenge firsthand. We have millions of insect specimens, each with a tiny, fragile label pinned underneath it containing vital data: where it was found, when, and by whom. To unlock this data at scale, I realized I needed a toolkit that didn’t exist in a traditional archaeologist’s repertoire.

In 2021, I took the plunge and enrolled in a Data Science course. It was an intense immersion into a world seemingly far removed from archaeology: algorithms, Machine Learning, and Natural Language Processing. Yet, I soon began to see connections. The computer vision techniques used for modern text recognition could be the “digital trowel” needed to unearth data from those tiny museum labels. The seeds for what would become ELIE were planted during my final capstone project: Handwritten Text Recognition and Machine Learning applied for the digitization of specimens’ labels in natural history collections.

The “Picturae” Challenge

The timing couldn’t have been better. The MfN had launched a massive digitisation initiative using a high-speed conveyor-belt system developed by the Dutch company Picturae. Between 2022 and 2023 alone, the museum digitised 650,000 specimens using this system.

Suddenly, our servers were flooded with tens of thousands of images per month. While the images were great, they created a new problem. We had the pictures, but the data on the labels was trapped in pixels.

In the museum world, we know that over 85% of specimen metadata resides on these physical labels or ledgers. Manually typing out the text for half a billion insects worldwide would take centuries. We needed a way to automate the reading of these labels without sacrificing the accuracy that taxonomists require.

Enter ELIE

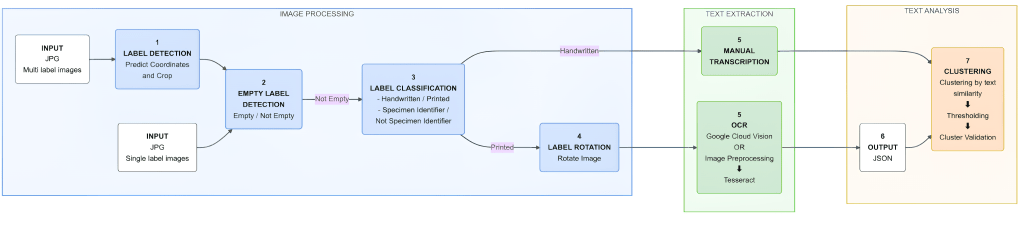

This is where ELIE comes in. In our Methods in Ecology and Evolution article, High Throughput Information Extraction of Printed Specimen Labels from Large-Scale Digitization of Entomological Collections using a Semi-Automated Pipeline, we present this pipeline as a modular solution designed specifically for entomological collections.

We built ELIE to think like a curator. First, it separates the easy stuff from the hard stuff. It uses a Convolutional Neural Network to distinguish between printed labels (which computers read well) and handwritten labels (which are notoriously difficult). This separation is crucial because, while Optical Character Recognition (OCR) is powerful, it still struggles with the variable, cursive handwriting often found in historical collections.

For the printed labels, we found that modern OCR tools like the Google Vision API were incredibly robust, far outperforming older open-source alternatives like Tesseract on our datasets.

But we didn’t stop at just reading the text. One of the nicest features, developed by my colleague Joël Tuberosa, is a clustering algorithm. Since entomologists often collect many specimens at the same place and time (a “gathering event”), many labels are identical. It makes no sense to type the “Amazonas, Brazil, 1998” location data 50 times. ELIE groups these identical labels so that a human only has to check one or two of them to validate the whole batch.

What We Found

When we tested ELIE on datasets from the MfN, the Smithsonian, and Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, we found that it could reduce the manual transcription effort by up to 87%.

On the printed labels, the pipeline achieved up to 98% accuracy in extraction and clustering. This means that for the vast majority of our modern collections, the computer does the heavy lifting. By automating the “boring” work of transcribing printed labels, we free up researchers and curators to focus on high-value tasks.

Looking Ahead

Of course, the work isn’t finished. The “white whale” of digitisation remains the handwritten labels, especially those from historical collections with faded ink and idiosyncratic scrawls. My experience with deciphering Sütterlin in the archives tells me this won’t be easy!

For now, ELIE sorts these handwritten labels out for manual review, but we are already looking at the next frontier. We plan to integrate specific Handwritten Text Recognition models and even Large Language Models (LLMs) to help interpret these historical puzzles. LLMs could help us not just read the text, but understand it, linking abbreviated locality names to their modern geographical coordinates or resolving outdated taxonomic synonyms.

This project has been a wonderful example of how interdisciplinary skills, combining traditional museum knowledge with modern data science, can unlock the history hidden in our collections. It turns out that the leap from digging up the past to coding the future isn’t as wide as I thought.

Read the full article here.