Post provided by Ravi Umadi.

On a humid, warm evening—close to 40 °C—in Mohali, India, I stood outside holding a bat detector, listening for something I had never heard before. Although I had never previously heard bat echolocation calls, bats themselves were not unfamiliar to me. One of my earliest memories from primary school is of a dark corner of my village school that housed a colony of Taphozous melanopogon—a binomial I would only learn many years later, in 2017, when I formally began working on bats.

Hearing the invisible

Seeing bats for the first time as a child and hearing their echolocation calls for the first time as an adult were experiences separated by years but connected by the same sense of curiosity. Shortly after sunset, while I was still fiddling with a Pettersson D1000X detector borrowed from the lab I was working in at the time, I heard a faint series of clicks. At first, it did not register what I was hearing. Then it happened again—a clear train of clicks through the heterodyne channel. I looked up instinctively. My head felt light with excitement. I barely slept that night, replaying the experience over and over in my mind.

How does it work?

Almost immediately, another question followed: How does this thing actually work? As a child, I had the habit of opening every mechanical toy before playing with it, driven by an urge to understand what lay inside. The supervisor who lent me the bat detector had warned me that it was expensive equipment and needed careful handling, so disassembly was clearly not an option. That night was filled with excitement, curiosity, and a faint discomfort at not knowing how the device transformed ultrasonic calls into something audible. That moment turned out to be a turning point. Soon after, I began scribbling equations, trying to understand how bats decide when to call and how often. Those early thoughts eventually grew into what I later formalised as the responsivity framework, which has since become the basis of a series of papers I began writing last year.

From curiosity to a device

Hobby electronics has always been one of my curiosities. At some point, I began to wonder whether I could actually build a bat detector myself. I started modestly, experimenting with a locally made, educational analogue bat detector kit. It worked. The kit came with detailed instructions, and assembling it was straightforward—but the sense of achievement was real. It gave me confidence.

Encouraged, I moved on to Arduino microcontrollers, hoping to understand how audio processing worked on these small development boards. For nearly six months, I made little progress. This was during a period when I was also working at a university hospital, building experimental prototypes for an orthopaedic surgeon. Those projects involved music playback, posture tracking, and inertial sensors using Arduino and ESP microcontrollers. Somewhere along the way, audio finally clicked. I began digging deeper into the I²S protocol, and over weekends and holidays, I experimented with recording audio using analogue MEMS microphones. I wrote simple C++ programs in the Arduino IDE, built basic recorders, and even managed to implement a rudimentary music player.

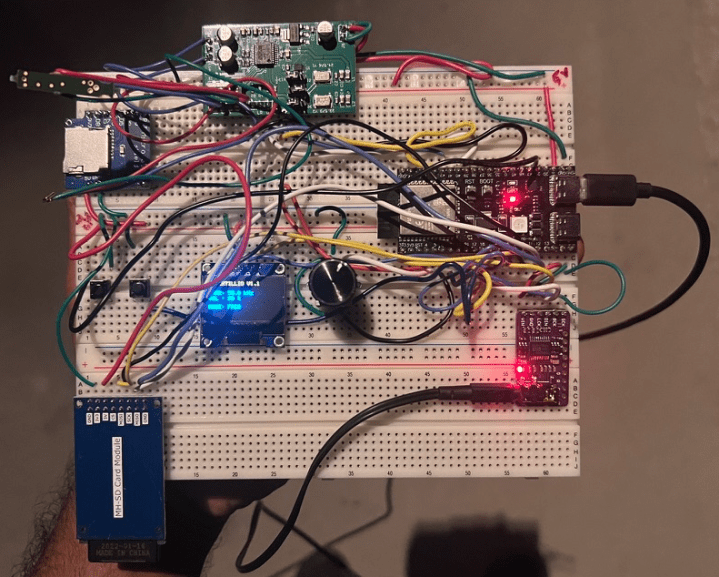

In the summer of 2023, I spent a month in a collaborator’s lab in Denmark. I remember packing my ESP32 circuit—still on a breadboard—into my luggage. In spare moments, I continued experimenting, gradually figuring out real-time audio processing on the ESP32. The moment it worked, I was elated. Suddenly, tasks that previously required MATLAB or Python scripts interfaced with a sound card could be executed on a €5 microcontroller.

There was, however, a significant hurdle. No publicly available library supported recording at 192 kHz. Existing I²S audio libraries were designed for consumer audio applications and fell short of what bat bioacoustics demanded. There was no alternative but to go deeper. I immersed myself in ESP32 documentation and low-level I²S architecture, learning through extended trial and error. Then, one spring evening, it finally worked. The spectrogram of a simple recording—jiggling keys—extended cleanly up to 96 kHz. That moment confirmed that high-frequency ultrasonic recording was possible on low-cost hardware; I became convinced that a portable, low-cost bat detector and recorder—built entirely from off-the-shelf components—was achievable.

After submitting my doctoral thesis in June 2025, I spent the entire summer building Esperdyne, along with its more specialised counterpart, Batsy4-Pro, designed for behavioural field experiments with a microphone array. Both devices feature live heterodyning, with Esperdyne offering independent, user-selectable tuning frequencies for each channel. The user interface was deliberately designed to be simple yet informative. Years of fieldwork had taught me what truly matters: a device that works immediately, with minimal setup, and no unnecessary configuration. Anticipating encounters with constant-frequency bats, I knew the system also needed flexible frequency tuning across bands. And when the field session is done, one needs simple software to hear the bat calls and sort the data; therefore Esperdyne comes with Bat Reviewer.

When everything was finally assembled, tested, and ready, I took Esperdyne out for its first field trial along the River Isar—where I often go for long thinking walks. It was a warm evening in August 2025. Soon after sunset, I heard the familiar train of clicks. The joy was familiar too. The excitement felt exactly like that first night in Mohali. As always, the satisfaction of seeing an idea come alive was worth every frustration along the way.

Read Ravi Umadi’s complementary blog post here.

Read the full article here.

Post edited by Sthandiwe Nomthandazo Kanyile.