Post provided by Marieke Wesselkamp

At the beginning of this project, we often found ourselves contemplating on the evolution of various environmental systems – some vast and global, others local. These were, for example, the trajectory of elephant populations in the Southern African Kruger national park over the next decades, the change in plant species composition on the roof the neighbour’s garage over the months, or the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, projected over the next billion of years. Despite their differences in scales and complexity, the reflections centred around the same question: What can we actually predict, and for how long? What can we know about the future, based on our current understanding? Motivated by these questions, we started investigating the relationships between uncertainty and prediction in ecological systems with the tool at hand: model simulations. And this path led us to draw inspiration from a field renowned for confronting the limits of predictability: operational weather forecasting.

Why study the forecast limit?

The importance of quantifying ecological predictability is growing in the face of climate change, where management decisions increasingly rely on model-based forecasts (Dietze et al. 2024). Even our best forecasting models are inherently uncertain about the future and increasingly so, the farther into the future they predict. But then, how much can we rely on these statements when decisions must be made over a relevant time horizon? Recent work in ecology has focused on comparing the predictability across models and systems and concluded that establishing best practices would greatly support this undertaking (Lewis et al. 2021). So rather than remaining in contemplation about what and how far we can predict, we turned to quantifying a model’s forecast limit (Petchey et al. 2015).

How does our approach work and does it work?

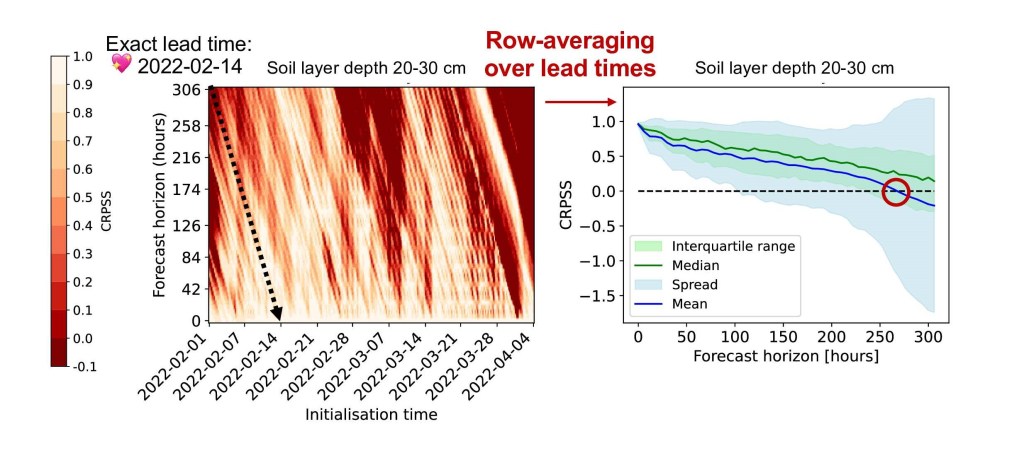

In our recent article (Wesselkamp et al. 2025), we introduce a framework for determining the forecast limit and distinguishing between three of its types. These are classified based on two criteria (1) the verification data used for evaluation and (2) the evaluation reference. At the core of this framework are reference models, also known as benchmark or null models (Pappenberger et al. 2015). Such models are essential to determine forecast skill: Is it better or worse than what we could expect a prior? Given a suitable reference model and a scoring function, evaluating the forecast skill over multiple lead times (Buizza and Leutbecher 2015) estimates the forecast limit. This quantifies the relative predictability of the system, conditional on the forecast model that is used.

One of the case studies in our article illustrates the concept of the relative forecast limit using a neural network land surface emulator that forecasts soil temperature and moisture at various soil depths (Wesselkamp et al. 2025). We applied this approach for one location in southern France (Condom-en-Armagnac) over the period from February to April and verified the forecasts with measurements from the International Soil Moisture Network (Dorigo et al. 2021). The results offer insight into the predictability of soil states support established theory: Soil temperature predictability is low at the surface and increases with depth as its dependence on forcing predictability decreases. Imprecise estimates of the forecast limit – particularly in shallow layers – indicates how short-term dynamics, rather than the forecast horizon, dominate model skill at the surface.

Why does it matter?

As a metric to quantify predictability, the forecast limit complements any ecological forecast. Moving beyond communicating of raw forecasts of a system state evolution or aggregated performance scores, the forecast limit provides deeper insight into where and when a forecast model is ‘good enough‘. When reported alongside model forecasts and verification scores, the forecast limit can support informed decision-making, especially when these depend on a specific time horizon and spatial context.

What’s next?

Predictability analysis relies on uncertainty propagation, which optimally is fully accounted for in a forecast, and the study of predictability may greatly profit from differentiable surrogate models such as the land surface emulators that enable gradient-based analyses. Moving there in future works may help detecting sources of ecological predictability, for example by determining which components currently contribute most to the forecast limit. Qualitatively, we can already get a hold on to this in our land surface case study: Whereas initial conditions are often the limiting factor in metrological forecasts, soil states predictability appears to be primarily driven by forcing uncertainty (Dietze M. 2017).

Read the full article here.