Post provided by Faith Jones, Helen Spence-Jones, and Caroline Greiser

Fieldwork is the foundation of ecological science. From observational and monitoring studies, to experiments done in complex real-world conditions, to ground-truthing models: we can’t hope to understand ecology if we don’t actually check what is happening in nature. The love of being outdoors has also attracted many of us to careers in ecology: fieldwork remains a source of joy, fascination, and inspiration, as well as a vital part of biological research.

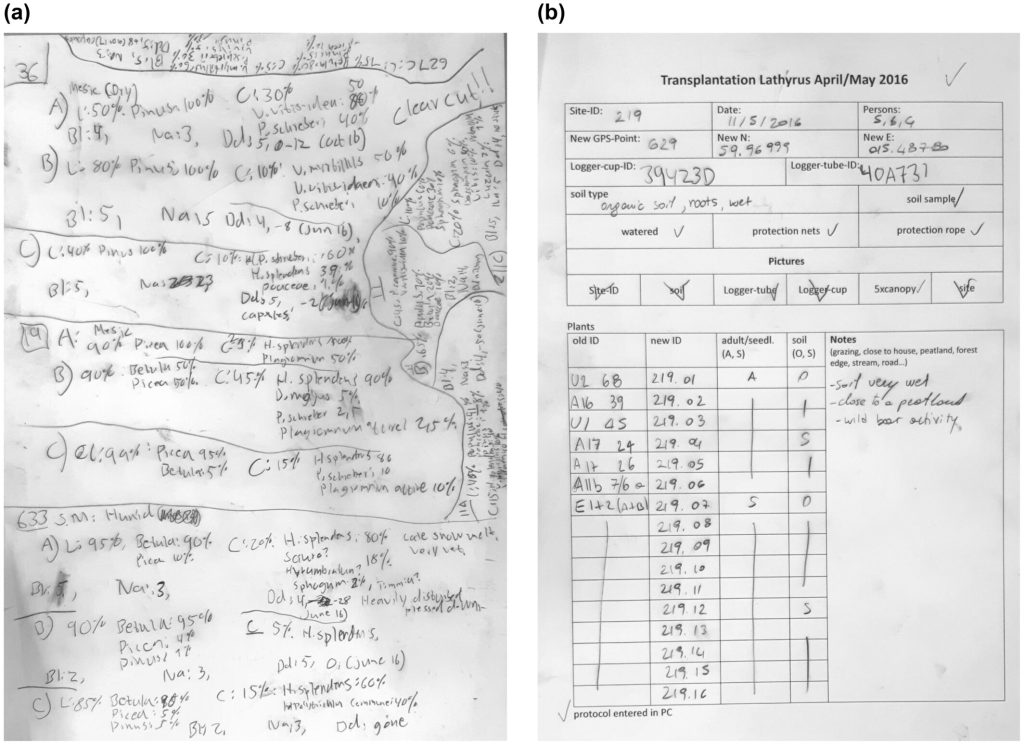

However much we might love it, field research is not always easy. Things go wrong. Things don’t work. Things break. Accidents happen. Lost data, mislabelled samples, incorrect records that don’t get caught, orphaned datapoints… It is all-too-easy to find a rogue sample in a freezer whose label makes no sense, and which no-one involved can remember collecting – or to realise an inconvenient software glitch has scrambled the metadata on a hard drive full of photographs with no other way of telling where and when they were taken. Such frustrations can happen to us all, and in some unlucky cases can seriously impact a study.

Of course, none of us are immune to bad luck, a moment of clumsiness, or a temporary error in judgement – and it is practically a rite of passage for new researchers to make some mistakes. Such missteps can teach us resilience, flexibility, and the noble art of sighing fatalistically and changing the plan for the seventh time that morning. They remind us that ecological research is complex: no matter how carefully we plan, there can always be an unforeseen factor or event that causes problems.

The three authors of this study have spent many happy days, weeks and months doing fieldwork. We’ve taken part in long-term monitoring and short-term experiments; we’ve stayed in permanent field stations and wandered into wildernesses with a backpack and a tent; we’ve recorded data with paper and pencil, cutting-edge gadgets, and even on devices that are now technically museum pieces. And none of us are strangers to things going wrong, or to hours – or even weeks – of scrambling to piece together or recover data afterwards. We remember some of our rookie mistakes with (painfully) vivid clarity, but happily we can laugh about them now: a sense of humour is sometimes an important field skill! At the end of the day, we have learned from our experiences.

But we believe that not all wisdom has to be hard-won. We wrote this guide for ourselves – or, more accurately, the junior versions of ourselves, setting out on our journeys with fresh-faced optimism and little idea of all of the interesting ways things can go wrong. We focused on pinning down the things we wished we’d known before we started: the small habits worth getting into that can save a lot of time and frustration in the long run, or that can be the saving grace when bad luck strikes.

Some of the things we came up with are designed to help avert problems, such as being careful about labelling consistency and making sure that all team members are aware of protocol changes. Others are about damage-control and recovery if something does go wrong, for example making backups and building redundancies into the data-collection design. A few count as both, like standardising data-collection routines or thinking explicitly about data structure.

Our list is neither comprehensive nor complete – and nor do we even always manage to follow our own advice! Still, we hope that it is useful as a starting point to spark discussions in lab groups and field teams: that it will be taken, adapted and extended for future field seasons and projects. And if it saves even one person from losing a dataset, or having to re-do a set of measurements at the end of a long day, or falling out with a colleague over whether a value is a ‘1’ or a ‘7’… then we consider it a success.

Read the full article here.