Post provided by Renske Jongen

The Rainbow Research series returns to the British Ecological Society to celebrate Pride month 2022! These special posts promote visibility and share stories from STEM researchers who belong to the LGBTQIA2S+ community. Each post is connected to one of the themes represented by the colours in the Progress Pride flag (Daniel Quasar 2018). In this post, Renske Jongen shares her journey on the way to studying seagrasses and their below-ground microbiome at the University of Sydney.

About me and my research

There we were, me and my best friend, sitting in the bushes with a dead mouse in front of us. Are we sure it’s dead? Were we really going to do this? Yep, we were, and it ended up being the gossip among the parents of the kids in my class.

The weird kid in school? Oh yeah, that was me. Instead of playing with dolls or barbies like most young girls do, I spent most of my time in the bushes looking for animals. Armed with a jar, a magnifying glass and a field guide on animals in Europe, I was determined to find all the animals listed in that book. The date of sighting and anything special I noted was carefully written down in a notebook. My desire to learn more about nature went so far that I even buried dead animals that I found, only to collect and study their skeletons later (I unfortunately never found any bones back…). That’s also how I ended up with that dead mouse I found. Only this time I wasn’t going to bury it, I wanted to study its anatomy. Me and my best friend decided it was a good idea to cut open that mouse and see what it looked like from the inside. I told you, I was weird.

Luckily, my weirdness didn’t hinder me much in making friends. I also had parents that encouraged my interest in nature. With my dad, I would spend my school lunch breaks catching frogs from the pond in the nearby forest, and my mom let me keep all kinds of animals as pets. Ranging from cats and birds, to lizards and albino African clawed frogs. She taught me to treat plants and animals with care and respect. Many weekends were spent washing cars to collect money for WWF, or collecting signatures to stop the wildlife trade. It may come as no surprise that I became a vegetarian at the age of 10, because loving animals and eating them at the same time made no sense to me. It still doesn’t by the way, and I became a vegan a couple of years ago.

At the age of four, I was convinced that I wanted to become a veterinarian. Later when choosing my bachelor program, I found out that studying biology actually suited me more. I wanted to know how nature works and save animals from extinction.

I’ll never forget Frederieke Wagner-Cremer, a professor at Utrecht University. She was the first professor during my bachelor’s that showed me that women in science can be inspiring AND funny. She has the most wicked sense of humour, and during her lectures most of the discussions where about environmental change. Ever since that course, this has been the central topic of all the research projects that I have worked on. She explained how the interactions between different organisms can change dramatically in response to climate change. To me this was really interesting; studying these variety of responses to climate change might help us understand which organisms are capable of adapting to the changing climate, and which ones may be in trouble.

For my master’s, I therefore ended up studying the seasonal timing of the winter moth, as well as fish behaviour in response to climate change. Right after my master’s I started working as a research assistant at The Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW), working on the interactions between plants and the soil. Working here made me realize that if I really wanted to save those animals I wanted to save as a young girl, the best way to do so is by conserving or restoring their habitat. And to do that, you need to know how that system works.

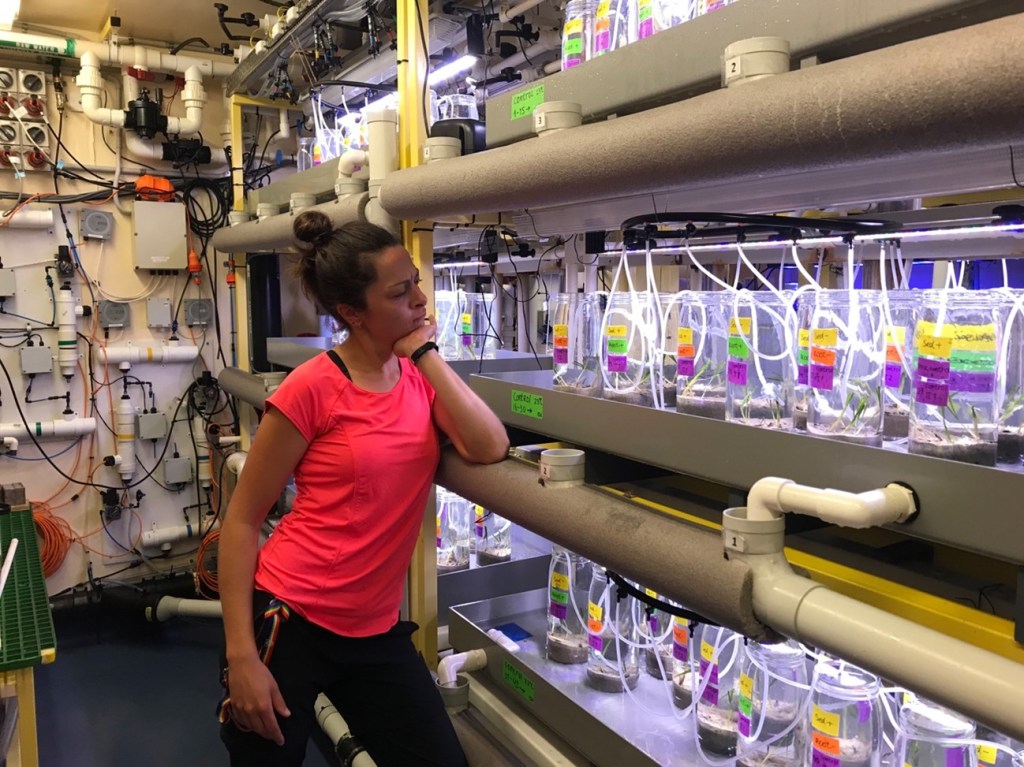

And here I am, doing exactly that. For my PhD, I moved from The Netherlands to Australia to study the interactions between seagrasses and below-ground microbes in the context of climate change. Seagrasses are marine flowering plants, that evolved from terrestrial plants and then returned back to the sea around 140 million years ago. You could call them the ‘whales’ of the plant kingdom. They are incredibly important because they support many other marine organisms by providing food or shelter, for example to sea turtles and dugongs. They also protect our coasts from storms, trap plastic particles and sequester large amounts of carbon. Unfortunately, seagrasses are not doing very well in a lot of places. In fact, we’re losing an area the size of 20,000 soccer fields around the world every year since the 1980’s as a result of stressors such as coastal development and climate change. You don’t hear so much about this compared to the loss of coral reefs or tropical rainforests, but these important seagrasses are actually one the most threatened ecosystems in the world. Lots of efforts are underway to conserve and restore seagrass meadows but often only have limited success.

Interestingly, most of the restoration efforts have only focused on improving above-ground conditions such as water clarity, while ignoring what is happening below-ground, in the sediment. For terrestrial plants we already know for quite some time that the soil, and soil microbes play an important role in the health of plants. For seagrasses not much is known about the importance of below-ground microbes for seagrasses, especially not in the context of environmental change.

For my PhD, I’m therefore studying these interactions between seagrasses and below-ground microbes, and see how these interactions change with climate change. If we know which microbes and what sediment conditions help seagrasses do better, then we can use that knowledge to improve restoration or monitoring techniques. I hope that my work will give some tangible outcomes that will help with just that.

My identity and what pride means to me

There are two main things that make up my identity: being vegan and a lesbian. As far apart as these two things seem to be (being vegan is a choice, being queer definitely isn’t), they actually share a lot of common ground. The link between identifying as non-heterosexual and living a plant-based life is that both don’t fit in the world’s view of society as it is now. Because heterosexuality and eating meat are seen as the normal and natural thing. Pride to me therefore means challenging and normalising identities and practices outside social norms. I don’t necessarily think that being queer or vegan should be celebrated. Simply by being open about it, I hope to open the eyes of the people around me to things that might seem ‘different’ to them. I want to help create a society that respects and embraces different groups of people and extending that to different species.

For that reason, I chose the colour ‘blue’ of the Pride Flag, which stands for ‘harmony’ as the best reflection of me and my research. In the end, everything in life is about combining all of our diverse and competing needs in such a way that the whole system works.

I was lucky to grow up in a non-religious family and a country like The Netherlands where people are usually pretty open-minded. I never really had a big coming out. After being in relationships with men for many years, I fell in love with a woman. I then realized that I preferred women over men and that was it. It should be like that for everyone. Unfortunately, the acceptance of homosexuality in society is often lacking behind despite major changes to the rights of LGBTQ+ people around the world. The same goes for animal rights or environmental change: must of us agree that something needs to be done, but the actual changes in society are happening too slow. I believe that the world could thrive if we all just had a little more understanding and respect for every human, animal and plant that is out there.

You can find out more about Renske and her research on Twitter and her website.

Want to share your Rainbow Research story? Find out more here.